Angela Merkel has two weeks to keep Germany’s centre-right together

The chancellor wins time to find a European solution to the immigration dispute rending her political alliance.

LAST week a dispute over immigration policy took Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats (CDU) and the Christian Social Union (CSU), their conservative Bavarian partners, to the brink of divorce. “I can’t work with this woman any more!” a furious Horst Seehofer, the CSU interior minister, fumed of the chancellor for blocking his proposal to turn migrants registered in other EU countries back at German borders. Open hostilities flew between CDU and CSU MPs, who sit in a single parliamentary group, in the halls of the Bundestag as the Bavarians refused to back down, pouring scorn on the chancellor’s request for two weeks to find a “European solution”.

But the weekend cooled heads and now détente has broken out. A meeting of the CSU leadership in Munich yesterday gave Mr Seehofer its blessing to impose the new border regime against Mrs Merkel’s will (whether or not the wording of the German constitution gives him the right to do so is debatable), but agreed that he would not act on this for two weeks, waiting to see the outcome of the chancellor’s European negotiations. For her part she conceded her interior minister permission to turn back refugees banned from Germany; albeit that measure is already mostly in effect.

The dispute is now stable, but not yet resolved. The CSU remains sceptical about the chancellor’s ability, at the EU summit on June 28th and 29th, to forge a long-elusive deal fixing the Dublin system regulating immigration to the EU, which grants responsibility for registering and processing immigrants to the member state where they first arrive. The Bavarians, whose state borders Austria and thus is the main entry point for those travelling north from Greece or Italy, accuse southern European states of waving through “asylum tourists” to Germany.

Mr Seehofer considers the long-term solution “anchor centres”, centralised immigration camps currently in operation in Bavaria, where applicants can be monitored and promptly deported if denied the right to stay. Until they are rolled out across the country, he reckons the only answer is to refuse entry to Germany to those registered elsewhere in the EU. How practical this would be is doubtful. The logistics of comprehensively manning, say, the 815km-long German-Austrian border, with its roughly 70 road crossings, are daunting. Whether Austria would readmit those refused entry by Germany is uncertain. Vienna might simply close its southern borders, prompting what Mrs Merkel described yesterday as a “domino effect”: a disastrous wave of unilateral border policies bringing down Europe’s free-movement regime. But the CSU’s goals are more than just practical: the party is also looking nervously at the state election in Bavaria in October, where the far-right Alternative for Germany threatens the party’s traditional hegemony.

What now? Mrs Merkel’s “European solution” will involve seeking bilateral deals with southern European states like Italy, Greece and Bulgaria to secure the prompt and automatic repatriation of immigrants from Germany to the states where they were first registered. These will not come easily: such countries feel they already bear an unfair share of the immigration burden. Indeed Italy’s new populist government, and particularly Matteo Salvini, its hard-right interior minister, is determined to reduce this burden at almost any cost. The chancellor will surely need to bring out her cheque-book. In her press conference yesterday she suggested she sees her existing cash-for-repatriations deal with Turkey, which has helped reduce flows of immigrants to Germany, as a template.

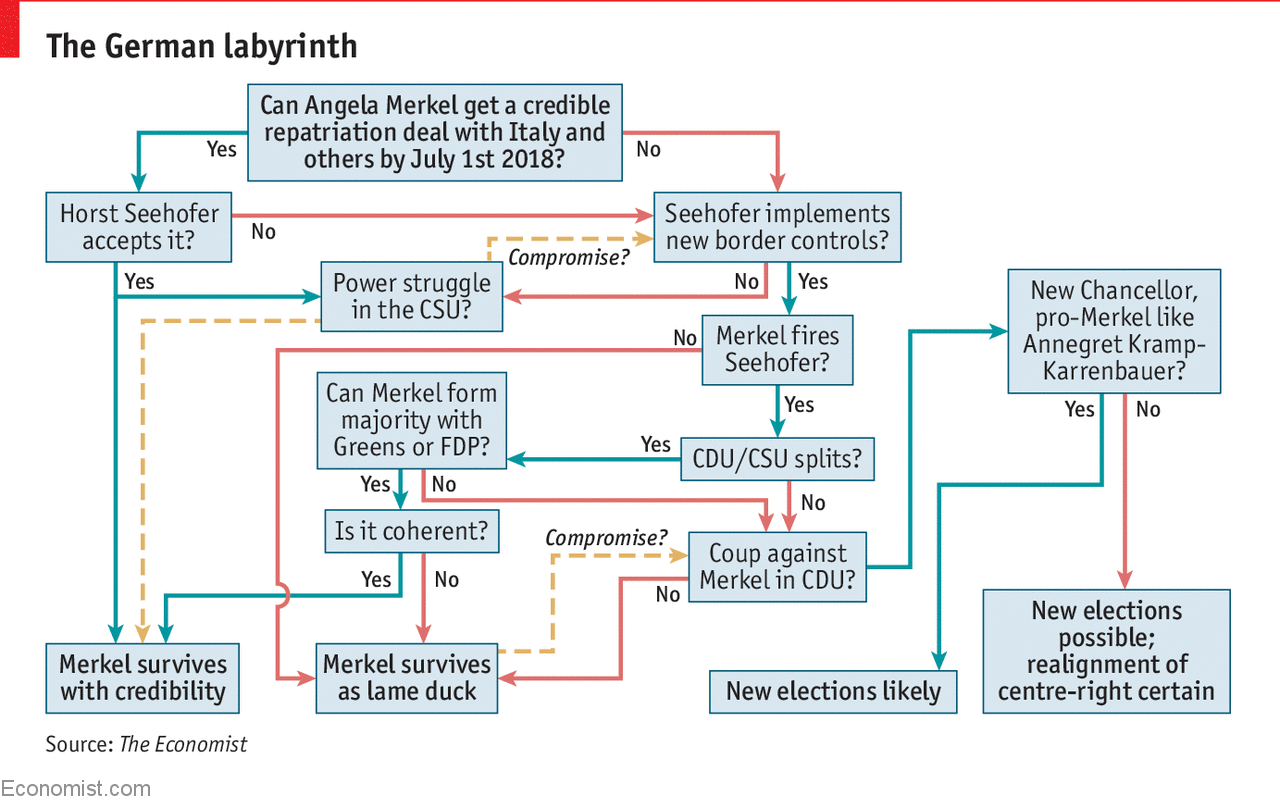

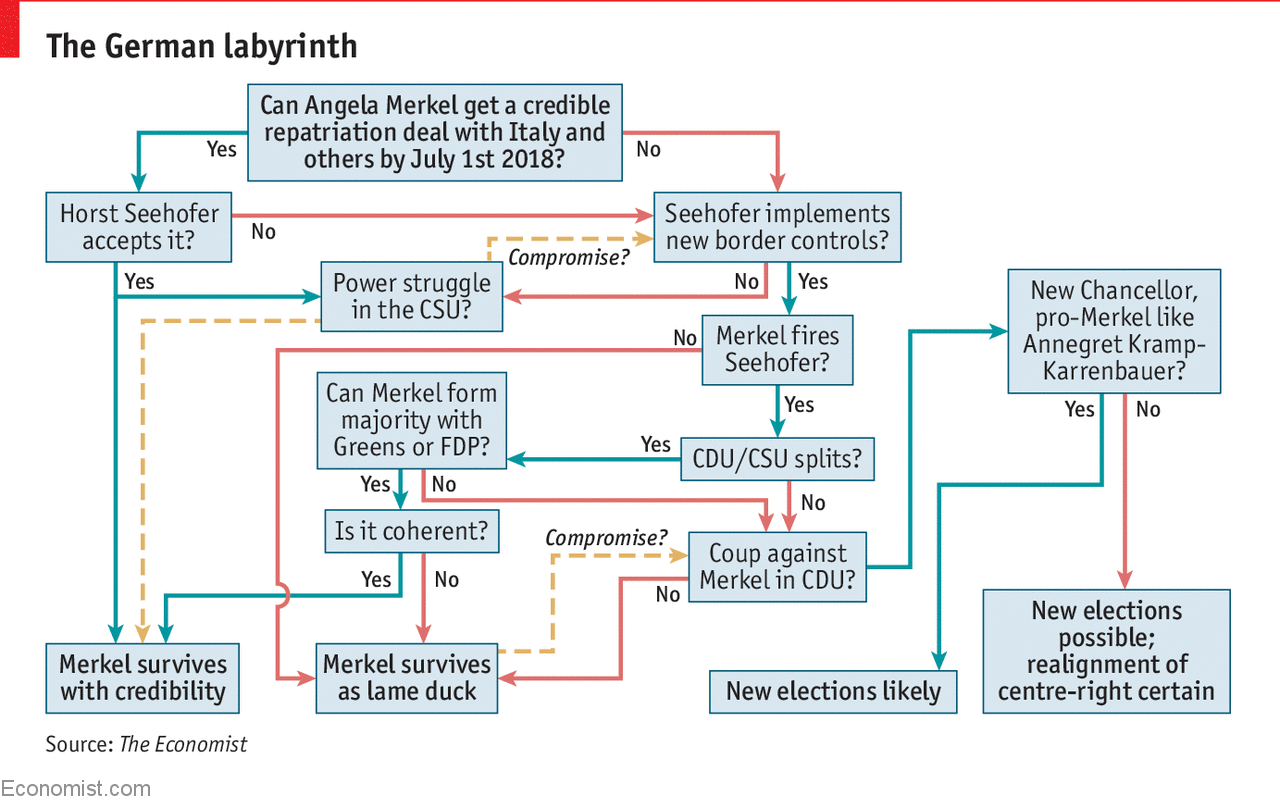

Following the EU summit late next week Mrs Merkel is due to present her achievements back in Berlin on July 1st. Then it will be up to the CSU to decide whether to accept them as substitutes for the threatened border policy, or whether Mr Seehofer should act unilaterally. The interior minister’s tough talk over the past days has left him little room to back down; he is in any case under pressure from Markus Söder, his long-time rival and the current prime minister of Bavaria, and Alexander Dobrindt, the CSU’s leader in the Bundestag, to keep up the pressure on the chancellor. Most likely is that Mrs Merkel will achieve enough in her European talks over the coming days for some compromise (perhaps involving step-by-step increases in border patrols and checks) to be reached with the CSU. But it is far from certain.

But if not? Mrs Merkel has made it clear that unilateral action by Mr Seehofer would be an act of war, yesterday stressing that the absence of a European solution should not automatically lead to the new controls and asserting that such matters were her responsibility as chancellor. All of which would make it hard for her to smooth over relations with any semblance of authority in the event of a unilateral move by her interior minister in early July.

In that event Mrs Merkel may therefore have no practical alternative but to fire him, which would probably eject the CSU from her coalition, leaving its remaining components (her CDU and the Social Democrats) just short of a majority. The Greens or the pro-business Free Democrats might be persuaded to make up the numbers, perhaps supporting the government in crucial votes without formally joining it. But Mrs Merkel’s authority would be greatly, perhaps terminally, diminished. She might stand down in favour of Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, the CDU general secretary and her preferred heir. A more disorderly departure might favour the chances of more Merkel-critical figures in the CDU, like Jens Spahn, the health minister and an ally of Mr Dobrindt.

Yet for now, as last week, a health-warning applies: do not write off Mrs Merkel just yet. The chancellor remains the most popular politician in Germany. She retains the support of most of her party; including that of a number of MPs not currently speaking up, to avoid further inflaming relations with the CSU, but who would stand behind her should her leadership come under dire threat. None of her possible replacements looks quite ready to step into her shoes yet (were this drama playing out in a couple of years’ time the picture might be different). The CSU’s tactics seem to be backfiring: polls show support for both the CDU/CSU nationally and the CSU in Bavaria falling. Many in the CDU, and some quietly sceptical moderates in the CSU, are losing patience with Mr Seehofer’s theatrics. It is one of the central rules of German politics that voters prize stability above most things. For as long as Mrs Merkel looks a better guarantor of that stability than her rivals, she remains a force to be reckoned with.