Trump used executive orders on several issues and Biden has sought to simply reverse his predecessor.

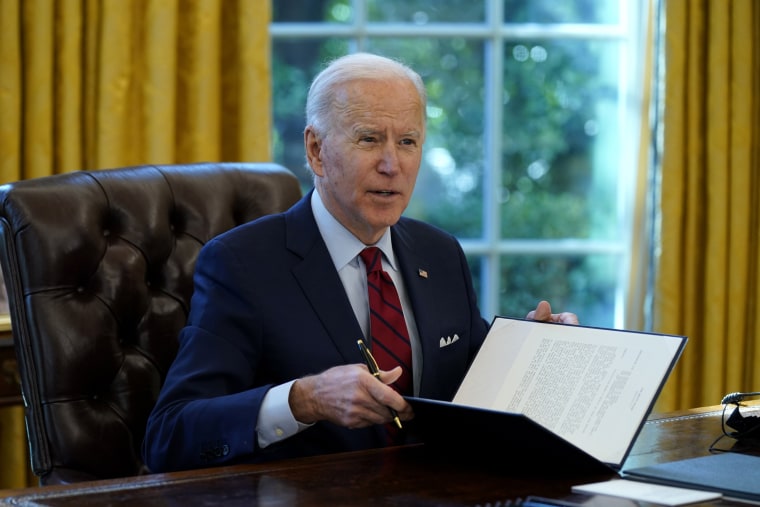

President Joe Biden signs a series of executive orders on health care, in the Oval Office, on Jan. 28, 2021.Evan Vucci / AP

President Joe Biden has signed a series of executive orders on a wide range of issues almost every day he’s been in office — from climate change to racial equality to curtailing the spread of Covid-19.

But for all the fanfare, it’s unclear how many are just symbolic gestures that will need legislative action in years to come. Congress, not the president, is tasked with making laws — a fact that Biden, who spent 36 years as a senator from Delaware, is surely aware.

“Big change, long-term change, less fragile change require legislation,” said Andrew Rudalevige, a government and legal studies professor at Bowdoin College who has studied presidential executive orders. Many orders also end up in lengthy court challenges, he said.

On the campaign trail, Biden frequently pushed back at demands from the liberal wing of his party for sweeping change by saying that he would need Congress to sign off on the largest changes.

The orders represent a White House effort both to reverse Trump Administration policies and to send an early signal to supporters that Biden intends to make good on his campaign promises.

Some of Biden’s executive orders have more of an impact than others. He has recommitted the U.S. to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change after Trump withdrew from it in 2017, for example, and reversed a Trump-era ban on transgender people serving in the military.

On Thursday, he signed an executive order to restore parts of the Affordable Care Act that Trump — through executive order — had dismantled.

But others Biden has signed appear more diffuse and aspirational.

One executive order directed governmental agencies to identify unspecified “actions” to address the current economic crisis resulting from the pandemic. It did not prescribe any specific actions.

Another order denounced anti-Asian discrimination and xenophobia. But it didn’t say how exactly that would be achieved.

Yet another calls on the Office of Management and Budget to “modernize and improve” the regulatory review process — but overhauling the regulatory review process was a top priority of the Trump administration, which worked for four years to change the system.

Experts point to the fact that executive orders are both simple to sign and simple to undo, creating confusion both domestically and internationally as one president is able to simply reverse policies enacted by another.

“The lack of continuity is an issue, and it does lead to a lack of stability for everyone from automakers to homeowners,” Rudalevige said.

White House advisers have been quick to defend Biden’s use of executive orders, particularly after The New York Times published an editorial Thursday urging him to “ease up” on the practice.

“We are not taking executive action in lieu of legislation: we are taking executive action to fix what Trump broke in the executive branch,” White House Chief of Staff Ron Klain wrote on Twitter.

“Of course we are pursuing our agenda through legislation,” White House Communications Director Kate Bedingfield noted, pointing to the $1.9 trillion Covid-19 relief plan the administration is negotiating in Congress.

Presidents since George Washington have used executive orders to advance their priorities, according to the American Presidency Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara. But the practice has become a flashpoint for controversy in recent years as Congress and the public have become more politically polarized.

Barack Obama sidestepped Congress to sign several high profile executive orders.

“I’ve got a pen and I’ve got a phone,” he announced in 2014, signaling that he would not wait for lawmakers to enact his agenda.

Obama’s most contested executive order, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, known as DACA, was an immigration measure he signed in 2012 aimed at offering limited legal status to some 700,000 immigrants brought illegally to the U.S. as children. The measure faced numerous court challenges and was effectively overturned by the Trump administration until the U.S. Supreme Court blocked Trump’s effort.

Trump took the use of executive orders even further, issuing almost as many in four years as Obama did in eight. Many of Trump’s orders, such as advancing the Keystone Pipeline and promoting a travel ban from several majority-Muslim countries, have been among the first Biden has sought to reverse.

[Disclaimer]