The deep distrust between Netanyahu and Gantz shapes every facet of the new coalition deal, transforming the nascent coalition into a two-headed hydra of contradictory impulses.

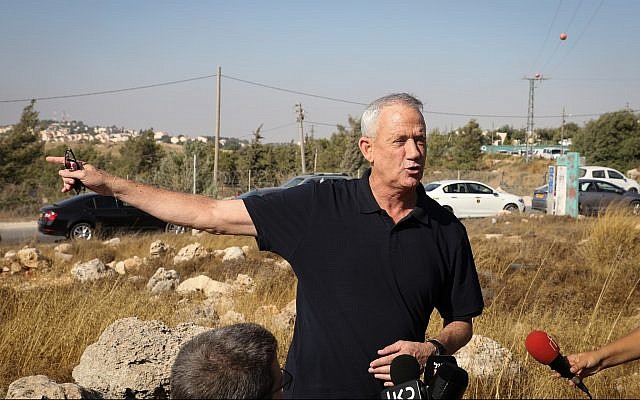

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Blue and White party leader Benny Gantz in the Knesset, November 10, 2019. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

Israel’s 35th Government began to come into focus on Monday with the signing of a coalition agreement between Benjamin Netanyahu and Benny Gantz.

And what a strange government it is.

In that it avoids a fourth consecutive election in the midst of a coronavirus pandemic, it may be a laudable achievement. But scratch the surface of the 14-page agreement and one finds that the “unity” government being celebrated by the two leaders is a bloated, bifurcated regime shaped by the deep distrust upon which it was built.

So much about the accord is unprecedented that it is best to simply set the term aside and just take things as they come.

The agreement sets the government’s lifespan at 36 months and divides it into two parts: a six-month “emergency period” and a longer “unity period” to follow.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, center, with Defense Minister Naftali Bennett of Yamina, Interior Minister Aryeh Deri of Shas, Health Minister Yaakov Litzman and MK Moshe Gafni of United Torah Judaism at a meeting of the heads of the right-religious bloc, at the Knesset, March 4, 2020. (Yonatan Sindel/Flash90)

During the emergency period, which Gantz and Netanyahu can extend in three-month increments by mutual agreement, no legislation can be advanced that doesn’t either contend with the coronavirus emergency or is approved by both men.

That is, for the duration of the emergency period, each has a veto on legislative initiatives.

Blocs

“The government will be a two-bloc government,” declares Article 2. And it isn’t kidding.

The government’s fundamental structure is shaped by the two alliances led by Netanyahu and Gantz, the “Likud bloc” and the “Blue and White bloc.”

This is no simple matter of optics. Gantz and Netanyahu are each granted enormous power over their “blocs.” Each can fire a minister from his bloc, a power usually reserved for the prime minister alone. And neither — even if they happen to be a prime minister — can fire a minister from the other’s bloc.

Blue and White leader Benny Gantz (left) and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu sign their unity government agreement on April 20, 2020. (GPO)

Similarly, to move an agency or some legal power from the hands of one ministry to another would normally require the approval of the prime minister. No longer: it is now the head of the relevant bloc who must approve the move. Whatever branch of government is granted to the “Likud bloc” under the agreement becomes Likud’s fiefdom and the same for Blue and White.

The government’s most basic structures, its most powerful committees — such as the security cabinet, which has the power to declare war, or the ministerial legislation committee — is divided between the blocs, with each bloc holding an equal number of members.

What little mention is made of specific policy priorities is also splintered along those lines. The right’s most prominent achievement — the coveted go-ahead for annexation of some unspecified portion of the West Bank — is also the only item on the new government’s agenda that Blue and White isn’t required to support.

Meanwhile, Gantz won nearly everything he needed in his bid to show that he was fulfilling his vow to “defend democracy” and liberal values.

Likud was disarmed of the three ministries from which it led its culture war against the left: justice, communications, and culture. Former speaker Yuli Edelstein, who defied a direct High Court order to convene a plenum vote on his successor (arguing it was an illegal imposition of the court’s will on the legislature) won’t return to the speaker’s chair.

Gantz did cede some ground on the Judicial Appointments Committee, responsible for selecting High Court justices. Though he got a member of his bloc on the nine-person panel, that MK, Derech Eretz’s Zvi Hauser, is a right-wing conservative who is likelier to side with the other bloc on such appointments, and could effectively give the right a veto on judge picks.

Benny Gantz (L) and Gabi Ashkenazi at a Blue and White campaign event in Kfar Saba on February 12, 2020. (Gili Yaari/ Flash90)